The Aden Withdrawal November 1967

Warrant Officer Godfrey (Jeff} Dykes

Royal Navy 1953 to 1983

Before 1966, I had visited Aden a couple of times and enjoyed both the naval facilities [Sheba, dockyard, Mermaid Club] and also the township of Aden proper. There were some good bars and reasonable eating houses. The Arabs were not unfriendly although I was never exposed to local customs and beliefs.

In 1966 whilst onboard H.M. Submarine Auriga, I spent a most enjoyable stay in Aden stopping there enroute for a long commission based on Singapore. From my diary of that time, I note that we arrived at 1340 on Sunday the 20th February when the weather was 85f. We were accommodated in the Merchant Navy Club, I in number 10 cabin, and after a diesel submarine, it was like being in the Ritz! Things had changed greatly since my last visit, and we were restricted to military sites only, for all our relaxation. Indeed, whilst enjoying the protection of Steamer Point, not far away in the village of Marla a local trades union man had been shot three times in the chest, and the next day a petrol bomb was thrown at an RAF officer's car but nobody was hurt. We had a good social programme visiting the 4/7 Royal Dragoon Guards mess at Little Aden; the Royal Corps of Transport at Normandy Heights, and we played rugby against RAF Khormaksar losing 38-0: that's good for a submarine crew!. We rewarded them by hosting a cocktail party in the submarine [limited numbers only] and then taking them to sea for a half day and diving to show them how hard our lives were compared to theirs - they readily agreed! The day before we left, 15 Arabs were injured by a rebel grenade and a serviceman was attacked and injured at Shiek Othman. We sailed for Singapore at 1600 on Wednesday the 2nd March after virtually eleven days of comfort and style. Little did we know that in time, we wouldn't be as happy the next time we saw Aden.

We crossed the Indian Ocean and arrived safely in Singapore where we were to be stationed until March 1968. It was a married accompanied draft, although being submarines we did more sea time than any other unit except for the fixed wing carriers, who were our equal, but without the smell and the heat of living in a veritable sewage tank. For the first two-thirds of the commission we had a good and happy crew, a crew who knew and liked the skipper well. He had been with us from the beginning, and together, we had worked the boat up into an efficient unit. Sadly, the day came for him to relinquish his command, and he was replaced by a most unpopular commanding officer. His attitude and unnecessary insistence on a 'new brush sweeps clean' approach, alienated many senior members of the crew, for they felt that their departments were already performing well, and they had just cause to believe that. Morale took a dive, and for the last third of the commission, it was a different boat.

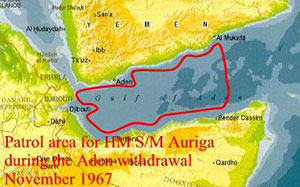

Then came the news that we were the nearest submarine to Aden [only over four thousand bloody miles away] and the British were planning to move out for good. Thus, at the end of October 1967, four months premature, our wives were ordered home, and we started our long and lonely trek across the Indian Ocean towards the Horn of Africa. We had just three days in Aden after travelling 4,300 miles, and then we were deployed immediately patrolling the Gulf of Aden. I have added a map here to show you our search box. The waterway you see to the upper left is the Red Sea, and far right is the sea area leading to the Indian Ocean. Aden is immediately above the letter 'l' in Gulf of Aden. It was our job as a sole submarine to patrol a relatively large search area to make sure that no surface or submarine units got anywhere near our boys and especially our big naval units, which conducted the major uplift and shift jobs of personnel, equipment and stores.

As always, the job was boring but of course necessary and we did it with a great sense of duty and dedication, happy to be there helping to write the pages of history. We were part of a Task Group, and the Task Group Commander flew his Flag in HMS Fearless, an LPD [Landing Platform Dock], and a very versatile amphibious ship at that. It could land fighting men by helicopters or by boats. To deploy the latter, she would submerge her stern so that the boats could navigate to the inside of the ship, and she was a large ship. She had a sister ship called the Intrepid which I will mention shortly. With her were aircraft carriers, and I was happy to know that one of my old ships, the Eagle, was there with the formidable punch of fixed-wing fighter aircraft. Other carriers were helicopters only, and they were mother and control ships to Royal Marine Commandos and other of their ilk leaving Aden for the last time.

This picture, which shows a task force of helicopters from HMS Albion and HMS Eagle, is the property of ex Warrant Officer John Eilbeck, whose permission I have to use it here. There are at least 15 helicopters and several ship, all there to move the British out of Aden as quickly and as safely as possible.

This photograph was taken at the end of the successful operation. It shows four units at anchor off Aden. The carrier Eagle, a commando carrier thought to be Albion, the flagship Fearless and us, submarine Auriga. I am on the bow, and the event was to cheer-ship for the CTG embarked in Fearless. Once the skimmers [pet name used by submariners for surface sailors] were safe and sound, we bade our farewell, and now without any form of leave or recreation for many weeks, we started our 4,000 odd mile journey back to our base in Singapore. However, on the way back we caused a major incident for ships and authorities in the Indian Ocean and the Far East proper. When submarines are on long passages it is the norm to dive for a few hours everyday to keep the crew on their toes

On this occasion, we [that's me by the way] sent a DIVING SIGNAL to our base in Singapore [HMS FORTH] to cover a series of DIVES on a pre determined TRACK for a given number of hours. At intervals, decided by our boss in Singapore, we were to send a report in the form of a radio signal bearing just the one word "CHECK", which signified that we were OK., and that we were safe doing our own thing, diving and surfacing at will. The time approached to send this signal, and the skipper gave me permission to start calling shore to pass this signal. I could hear Singapore loud and clear [his call sign was GYL] but he couldn't hear me. I could also hear lots of other stations from all areas of the world [Simonstown in South African call sign ZSJ down to our SSW; Malta way-up NW in the Mediterranean call sign GYX, dear old UK [where my wife was] call sign GKL, and various Australians the most prolific being call sign VHS many thousands of miles away to the east. None of these could hear me. I kept trying, changing frequencies to meet the prevailing conditions [a thing called the ionosphere] but still no luck.

Submarine aerials were not the most efficient devices, ours often taking in a goodly measure of sea water especially when we had done very little maintenance [but a lot of work] in the weeks gone by, although quite often the main radio transmitter did help to 'burn-off' some of this dampness, it acting as a 200-watt heater. During my endeavours to attract the attention of one of the above mentioned radio shore stations, I was pestered, yes, pestered, by local radio stations just north of us in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, vying with each other to take my precious CHECK report ostensibly for them [the one I chose] to pass it on to Singapore. I could talk for hours on the danger of falling into such a trap, but I can sum up the outcome in a simple way. It would have been better for me to leave my wireless office, climb to the top of the conning tower, screw the piece of paper on which was written the one word CHECK into a tight ball before throwing it into the sea below: it would never have reached our base commander either that way or via the route of the enthusiastic Asian operators sitting in Bombay, Karachi, Vishakhapatnam and Chittagong. That said, as the clock ticked away and the CHECK TIME grew ever closer, the skipper made the decision that I should pass the CHECK REPORT ashore to Karachi, he considering the Pakistan Navy to be the best of the bunch. As soon as I had received a ROGER for the signal, I began to get that sinking feeling. Nevertheless, I was being pessimistic without cause [except for my previous experiences and those of other RN telegraphists] because there was still time for them to pass the signal to Singapore.

The CHECK TIME came and went and HM sub Auriga was unaccounted for whilst crossing a very deep ocean. The authorities in Singapore were concerned, and after weighing the odds, issued a SUBMISS [Submarine Missing] signal which lead to a general alert by everybody east of Suez, including our friends back in Aden who we had supported for the withdrawal. Whilst we wallowed on the surface, at first unsure that our CHECK REPORT had made it, then fully aware that a SUBMISS signal had been sent when we read our BROADCAST ROUTINE, it was left to me to try and communicate with the outside world to quickly circumvent a situation developing whereby the whole world would be holding its breath concerned about our fate. As the hours wore on, we finally made contact with HMS Intrepid, the sister ship to HMS Fearless previously mentioned above which had left Aden sometime after us and was also heading for Singapore. Her commanding officer was a well known submariner called Captain Anthony Troup, Royal Navy , a larger than life figure, and he was as glad to see little old us as we were to see him in his mighty big warship. HMS Intrepid had a whole host of sophisticated radio equipment, with dry and efficient aerials being fed by high powered radio transmitters using techniques other than Morse code, and she radioed ahead to Singapore direct that all was well. The situation was saved and the withdrawal of the SUBMISS was a relief to all, and the more so for us. The kindly man sent across some fresh food and of course, a bottle for the skipper, then he went on his merry way to Singapore, leaving us to send a new DIVING SIGNAL and to continue our easterly journey spending a couple of hours per day down-under below the waves.

Whilst involved in the planning and execution of our duties in support of the Aden withdrawal, the potential problem of less than good morale had almost gone away. However, for some, as the miles to Singapore reduced, and despite the excitement of the missing CHECK REPORT, our thoughts turned to our wives and families, but at the same time, not unnaturally, we looked forward to getting back on terra firma and having a good submariners-type run ashore. It had been many weeks since our last relaxation, and seeing the back of that 'living coffin' was all that mattered. We were grateful that we would be spending Christmas ashore and not at sea.

Then came the 'bomb shell' which demotivated many on board. As we arrived, there on the jetty, was the skippers wife. The skipper was overjoyed, but soon got the message that we were not too pleased about seeing her still in Singapore. That money talks, and he had enough to keep his wife there privately is well understood, and it was his private business. But his cardinal mistake was not understanding what his selfish action would do to the morale of his men, including I might say, some of his more verbal officers. Fortunately for us, the majority of submarine skippers would not have made that same gaffe.

There I will finish because the story is, after all, about Aden, and not about the story of a submarine.

Suffice to say that we turned Sembawang, Nee Soon and other places upside down, and the Singapore breweries had to work overtime to replenish the island's depleted stocks of Tiger. Given the chance, we would have exchanged all this for having Christmas 1967 with our families.

The navy eventually felt sorry for us, and allowed us to go home east across the Pacific, calling at the Philippines, Guam, Hawaii, Acapulco, Panama, West Indies, and Bermuda. We had a ball and willingly forgave the Navy for interrupting our lives. We didn't forgive the skipper!

Godfrey (Jeff)

Dykes Royal Navy